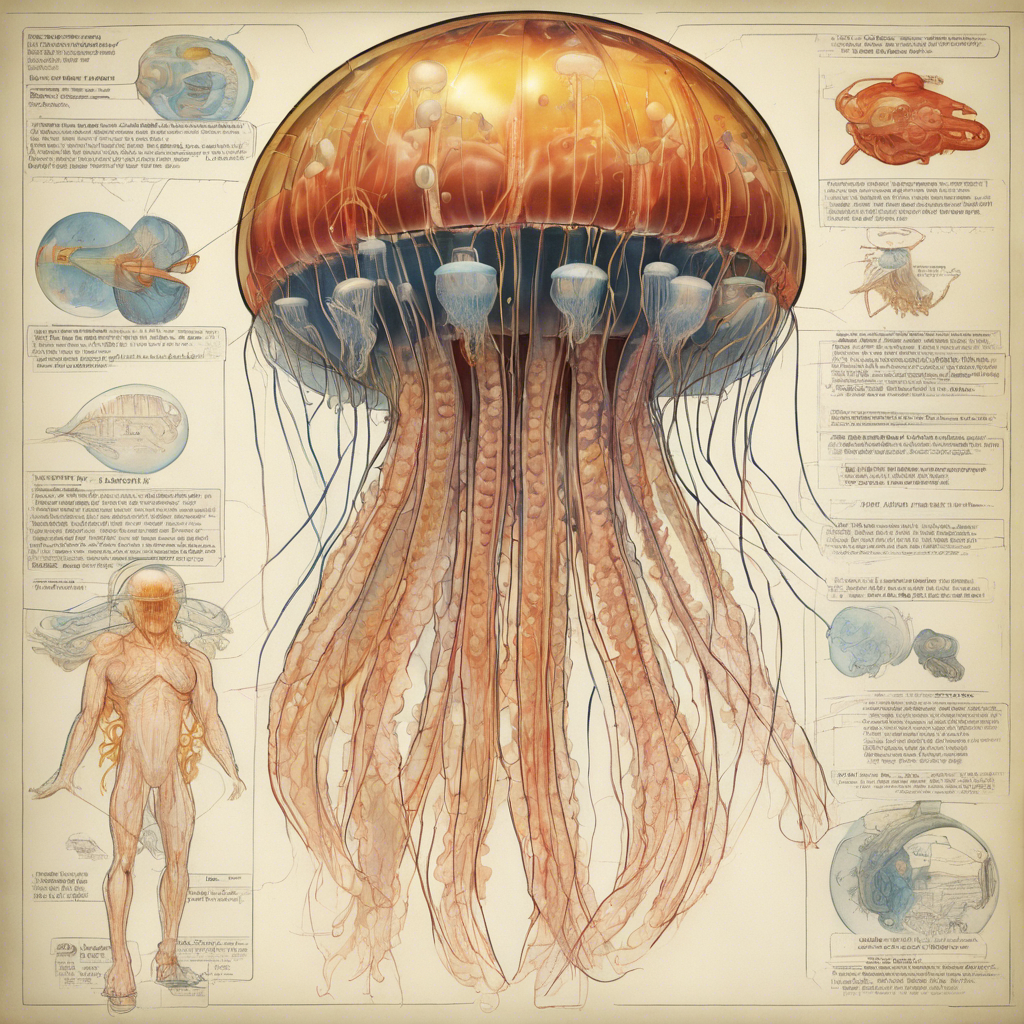

Lorsqu’un tentacule de méduse m’a tatoué sa lancinante marque érubescente sur le front, l’année dernière à Marseille, j’ai été sonné pendant deux heures et je me suis demandé si en plus de la douleur, cet accident ne pourrait pas me conférer de petits superpouvoirs. C’était bien arrivé à Peter Parker — je me voyais déjà flotter à la dérive, les filaments en éventail, méduse-man ne glandouillant rien, mais à la perfection. Et puis en reprenant mes esprits je me suis dit qu’on était en quelque sorte finement réglé par l’évolution, un peu comme une horloge ou à une chaîne hi-fi, et qu’il y n’y avait quasiment aucune chance pour qu’une petite modification accidentelle, du genre de celle conférée par une piqûre de méduse, améliore notre fonctionnement. Essayez d’inverser deux câbles au hasard dans votre chaîne hifi ou de tordre un engrenage dans votre montre suisse, pour qu’elles marchent mieux…

Dans ce papier publié dans un numéro spécial du Journal of Consciousness Studies dirigé par F. Kammerer et K. Frankish, que je résume pour le blog Imperfect Cognitions (merci Lisa Bortolotti), j’utilise ce genre de considérations pour rejeter une vieille idée, très prégnante chez les romantiques et jusque dans la psychopathologie phénoménologique ou la première psychiatrie évolutionniste, une idée dure à cuire que l’on peut faire remonter au moins au Phèdre de Platon et à un court essai sur le génie et la mélancolie attribué à tort à Aristote qui attribue des superpouvoirs cognitifs à la folie (je dis « au moins à Platon », car je connais mal l’Ancien Testament, lequel doit bien, j’imagine, assimiler quelque part les prophètes et les fous, et préfigurer le « délire divin » de Platon).

(Cet article a été publié en réponse à un article cible de K. Frankish et F. Kammerer, ils répondent ici)

When a jellyfish tentacle tattooed its throbbing, red mark on my forehead, last year in Marseille, I was stunned for two hours, wondering if, in addition to the pain, this mishap might endow me with superpowers. After all, it had happened to Peter Parker—I could already see myself floating aimlessly, tentacles spread out, being Jellyfish-man, lazing about doing absolutely, but absolutely nothing perfectly. Then, as I regained my senses, I thought that we are, in a way, finely tuned by evolution, like a clock or a hi-fi system, and that there’s almost no chance that a small accidental modification, like the kind from a jellyfish sting, could improve our functioning. Try to invert some random cables in your hi-fi system or to tilt some gear in you swiss clock to make them work better…

In this paper published in a special issue of the Journal of Consciousness Studies, edited by F. Kammerer and K. Frankish, which I summarize for the blog Imperfect Cognitions (thanks to Lisa Bortolotti), I use this kind of consideration to dismiss an old idea to the effect that madness confers some kinds of cognitive super-powers. This idea is a tough nut to crack. It can be traced back at least to Plato’s Phaedrus and a short essay on genius and melancholy wrongly attributed to Aristotle, and is still very prevalent among the romantics, in phenomenological psychopathology or early evolutionary psychiatry, (I say that it can be traced back ‘at least to Plato’ because I’m not well-versed in the Old Testament, which I assume somewhere equates prophets and madmen, foreshadowing Plato’s ‘divine madness’).